Essay - Amulets & Talismans Evolved

Brooke Barnett

Ethos

Amulets and Talismans Evolved 2021

Introduction.

‘Amulets, also called Talismans, an object, either natural or man-made, believed to be endowed with special powers to protect or bring good fortune.’ (Encyclopedia Britannica, 2021)

The terms Amulets, and Talismans, are usually used interchangeably, although according to “The complete book of amulets and talismans”, The word talismans is derived from the Greek “Root Teleo” which means “to consecrate” And it is precisely the act of consecration that which gives a talisman its alleged magical powers. For contrary to the amulet, which is usually an object naturally endowed with magical properties.’ (Wippler 1991, p.203.)

Natural amulets take the form of many things, such as stones with a naturally occurring hole through the centre, known as Hag stones, used for prevention of nightmares, or even a rabbits foot, kept oneself for good luck.

Man-made talismans can include religious symbolism or carved figurines. Amulets are said to derive power from their connection with natural forces, religious associations, or even from being made ritualistically, this can be seen in a Roman piece of carved agate, featuring a scorpion that was believed to protect the wearer and cure poison.

One might say that these items hold power because we assign it to them. As with many things, the reasons as to why we do this has changed over the course of time linked to cultural, socioeconomic and religious changes. Eventually many of the original beliefs attached to these items are forgotten as they become less relevant to the current day and age.

During the Victorian period and the rise of mourning jewellery, as many superstitious beliefs started to give way to science and modern medicine, the way people valued old amulets and talismans and assigned them meaning, transferred in a more sentimental way such as to ensure the survival of a lost loved ones essence in this new form of amulet.

If we look closely at why these items were valued so highly, we can perhaps focus on a missing link in the creation of modern day jewellery, and the problems that our current society has with fast fashion and how we view our jewellery now.

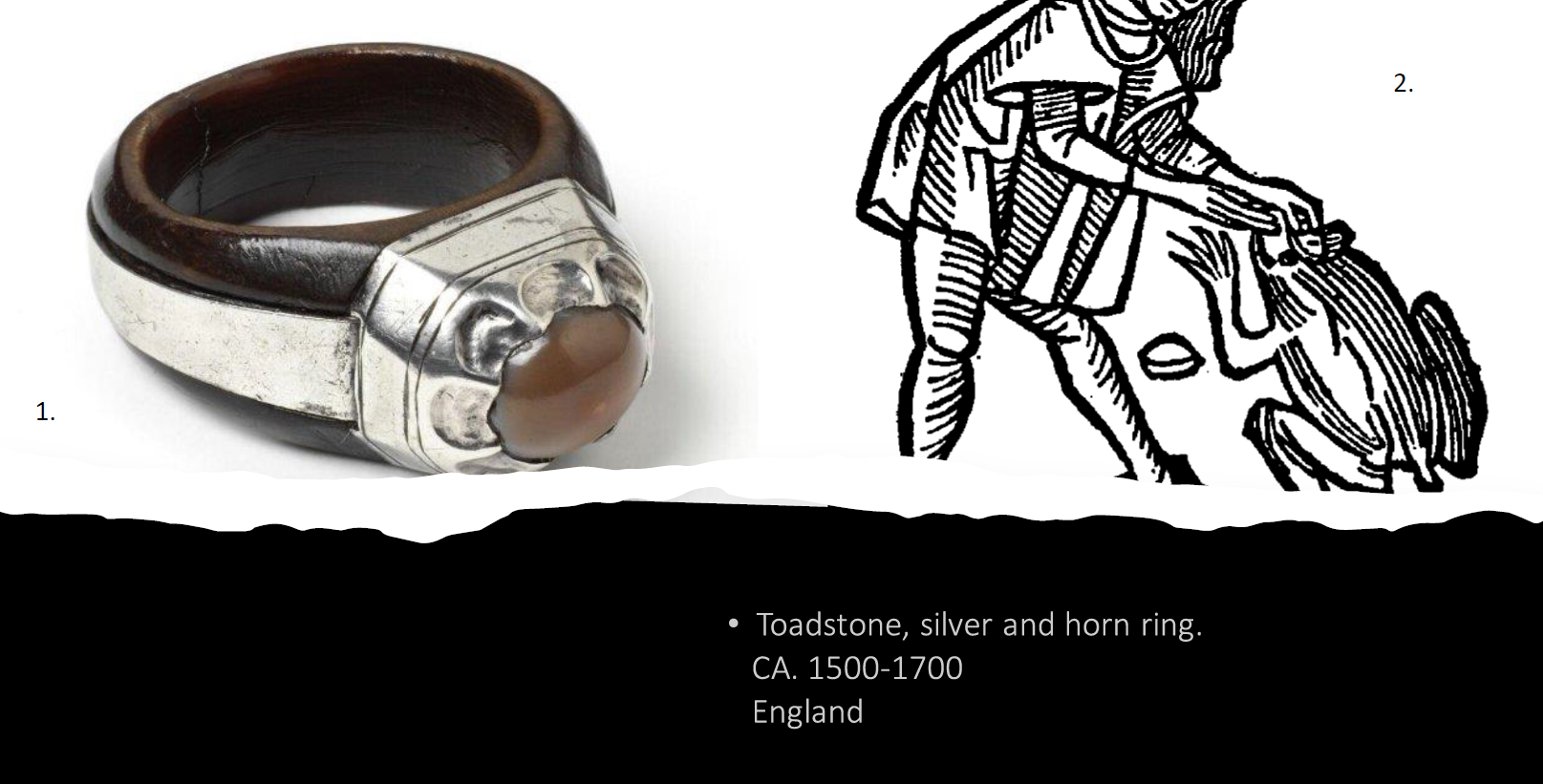

Toadstones are a perfect example of a talisman and were incredibly popular during the Middle ages and well into the Renaissance period.

The naturally cabochon shaped toad stone, ‘was believed to be effective against kidney disease and was a sure talisman of earthly happiness.’ (DeCuba, 1498.)

As knowledge evolved over the years, we now know that toad stones are actually the fossilised teeth of the Lepidotes fish from the Jurassic and Cretaceous period. We may not wear one to cure kidney disease, but the intrigue of these once potent pieces remains.

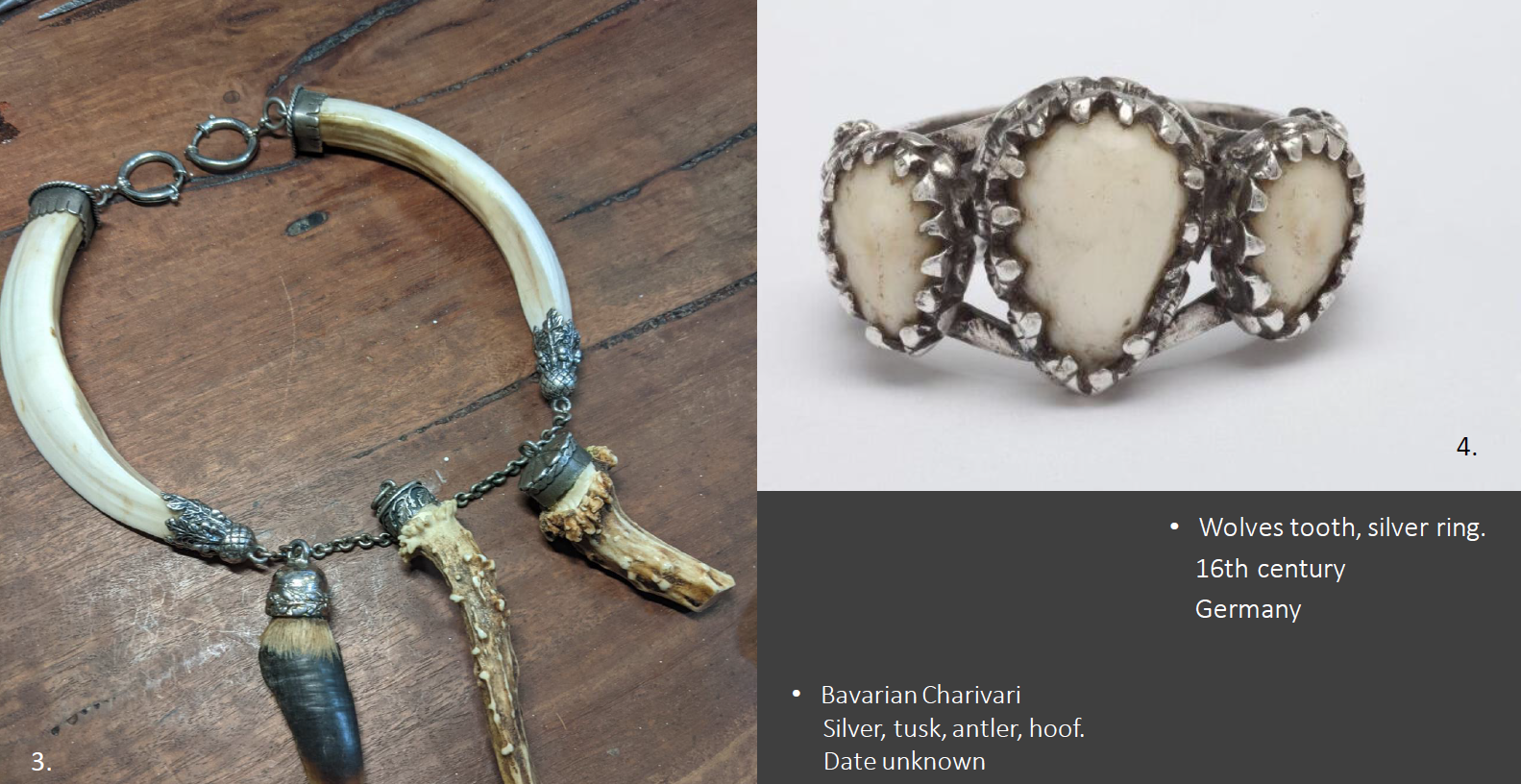

‘Teeth from predatory animals such as bears and wolves may have been favoured as a means of appropriating some of the strength and power of the animal and may have been used as amulets. In medieval and early modern Europe, wolves' teeth were thought to protect babies and help with teething.’ (Bury, S, 1984,p.26.)

This 16th century German made silver ring features three teardrop cabochons carved from wolves teeth.

Made in a very similar style is a piece from my personal jewellery collection, a Bavarian Charivari. Made from 835 silver, these were traditionally worn by the men to ensure a successful hunt and as seen in this piece, made from boar tusks, deer antler and hooves. I can personally speak for this talisman and have experienced the magic it holds from its mysterious past. What did each charm represent for the owner? Was it treasured and passed down for generations? All I can do is imagine and research, slowly I’ve begun to add my own charms and keepsakes to this piece, as to ensure the visual representation of storytelling from a certain time and place is passed on.

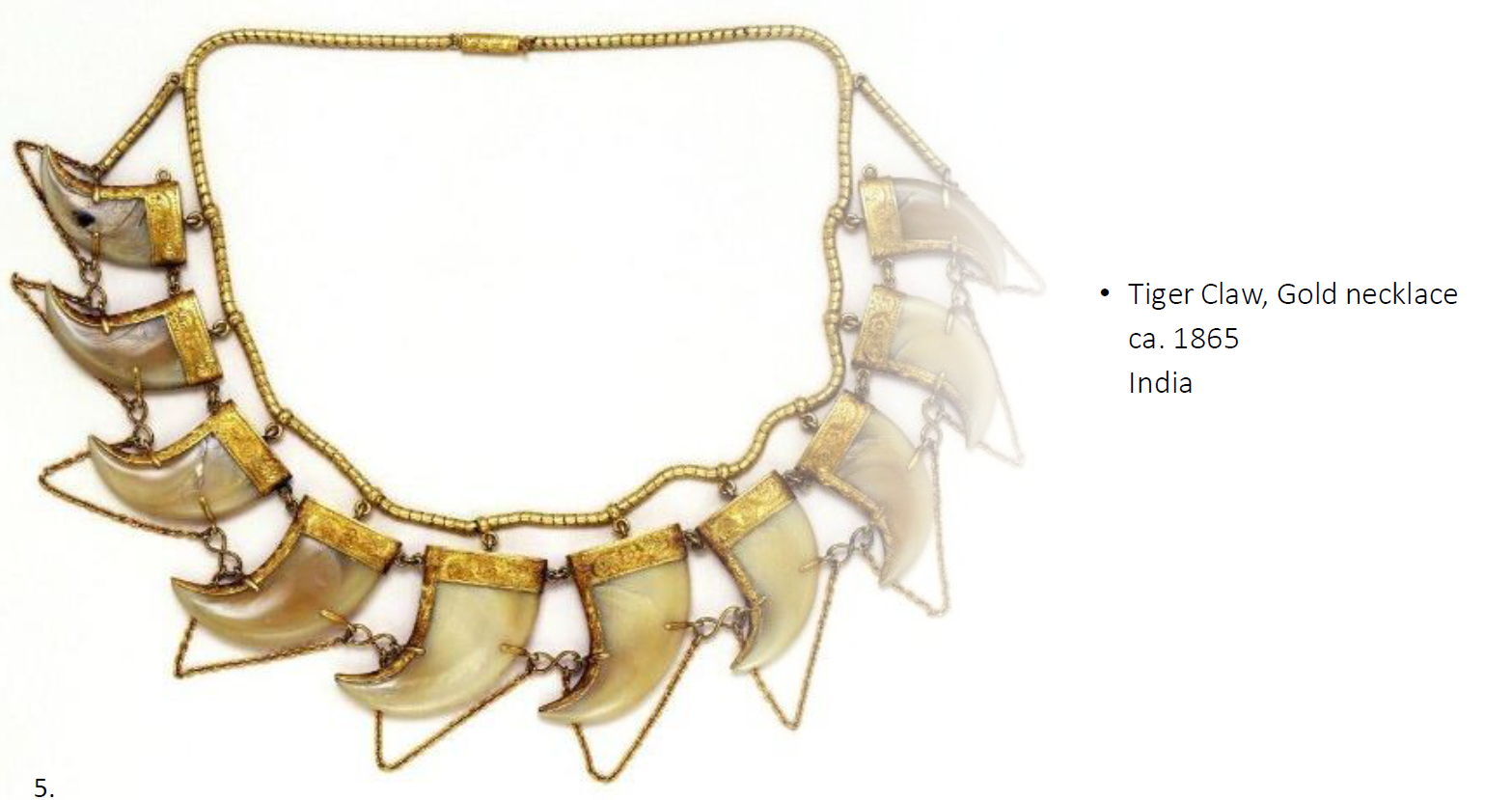

‘Tiger claws were regarded as charms against evil in India and were originally used as amulets. In her 1850 autobiography, Mrs Fanny Parkes, an English woman who lived in India between 1822 and 1846, describes observing and copying this custom. Tiger-claw jewellery was also made for the British, perhaps as an exotic souvenir of their lives in India. This necklace would have been made in India for the European market rather than for traditional use.’ (Stronge, Smith, Harle,1988.)

The importance associated with the power of the tiger claw, even if not necessarily believed by Mrs Fanny Parkes was something that was taken and interpreted in a new way to better suit her culture.

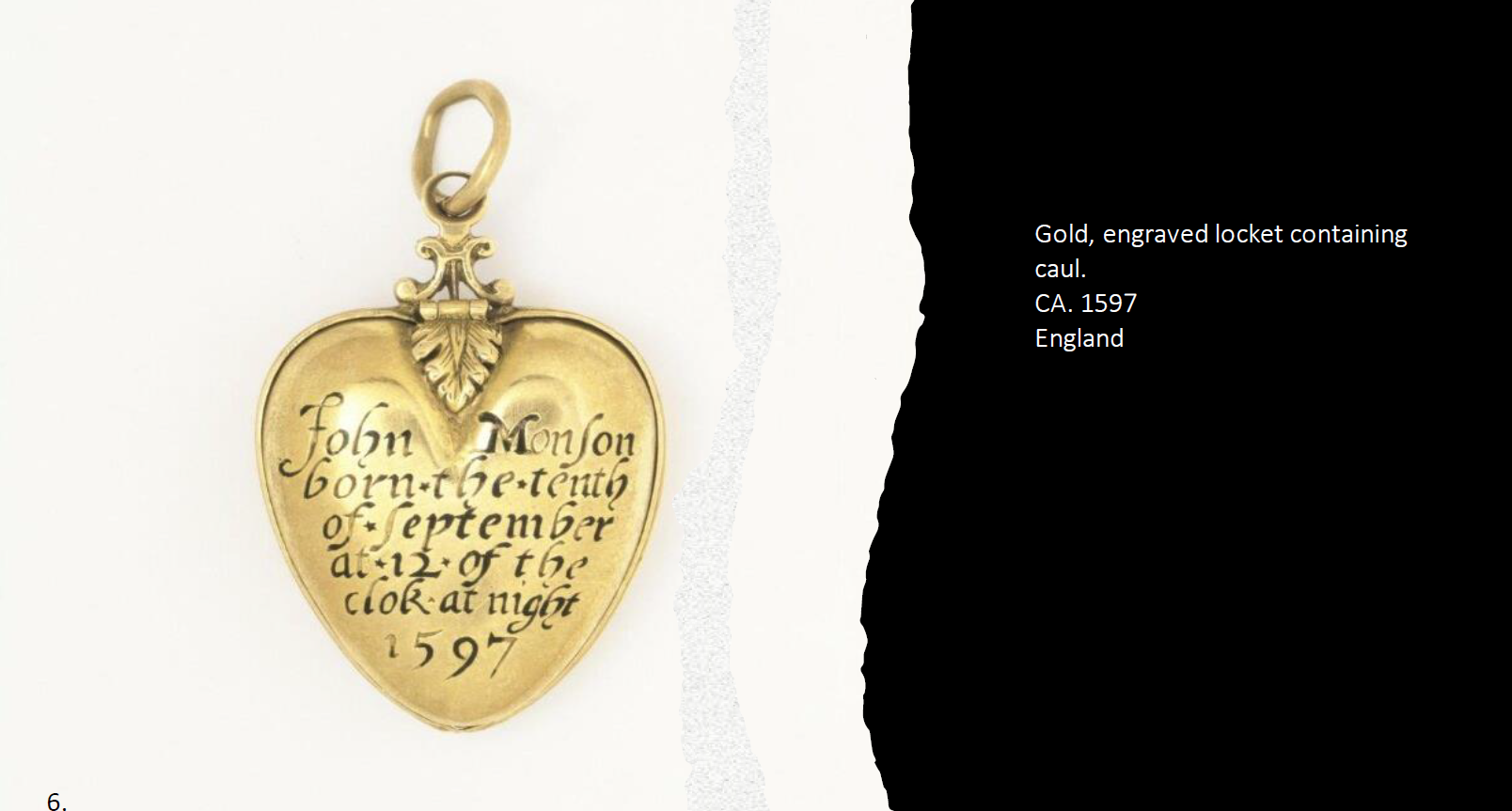

This gold locket contains part of the caul that John Monson was born with in 1597, as engraved on the front. Those born with the caul in nineteenth and twentieth-century England were considered safe from drowning.

‘If the caul was sold, its protective power was transferred to the new owner. Notices in newspapers and dock-side shop windows abound advertising this popular amulet; in 1835, the London Times marketed “a Child’s Caul to be disposed of, a well-known preservative against drowning, &c., price 10 guineas” (Moore,1891.)’ (Thwaite, 2019.)

Did John Monson pass on his locket to a loved one after death? Was it perhaps kept also as a form of mourning jewellery due to its close association to the deceased?

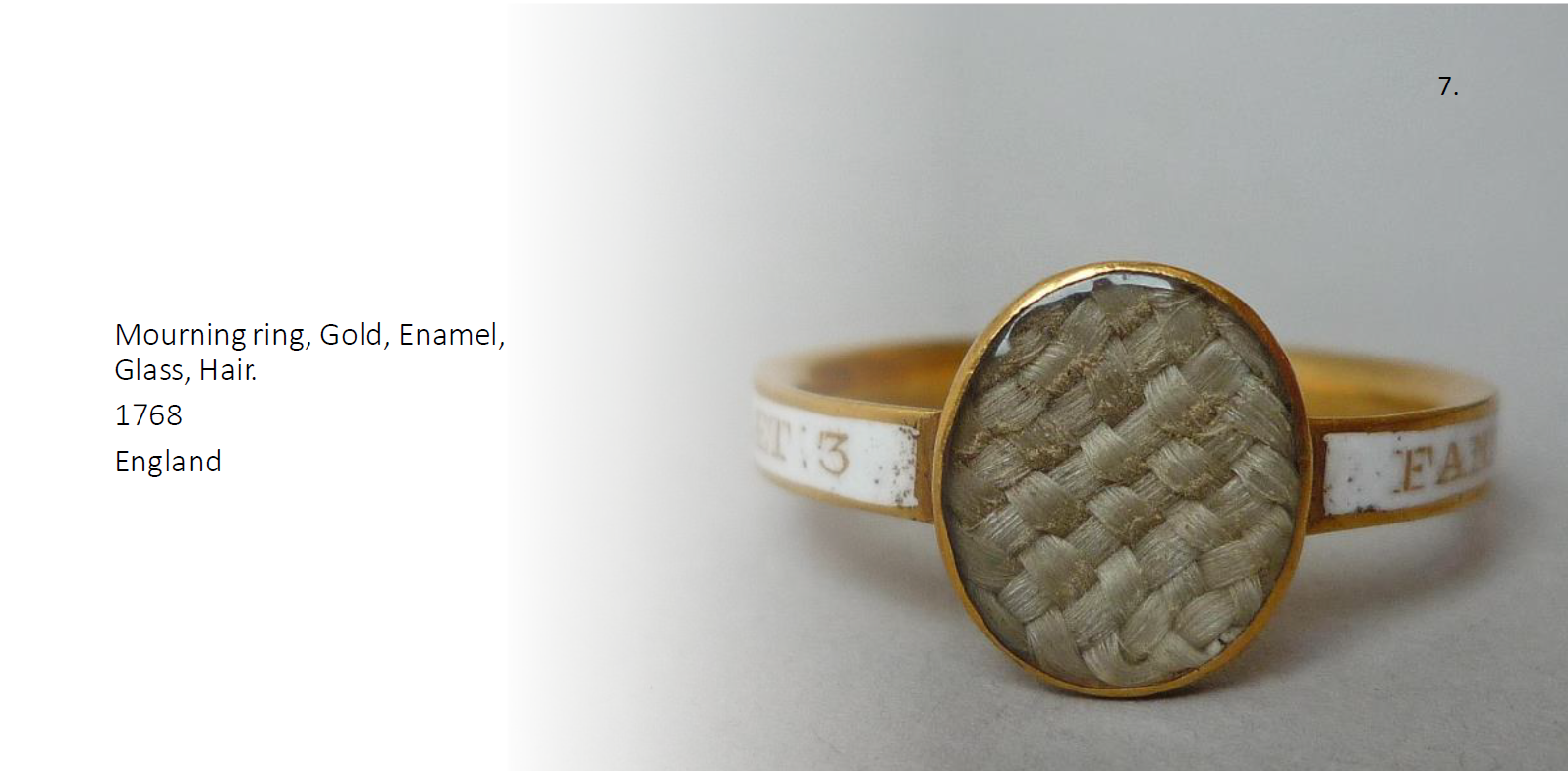

Mourning jewellery has been around since the middle ages, somewhat linked to the Memento Mori movement, Latin for ‘remember you must die’. It became incredibly popular during the Victorian period after Queen Victoria mourned the loss of her husband Prince Albert.

This 18th century gold ring includes an inscription on white enamel, an oval bezel contains plaited hair beneath the glass. Hair supposedly held an immortal quality that contained the essence of a person and would serve as an invaluable keepsake to those remembering a loved one.

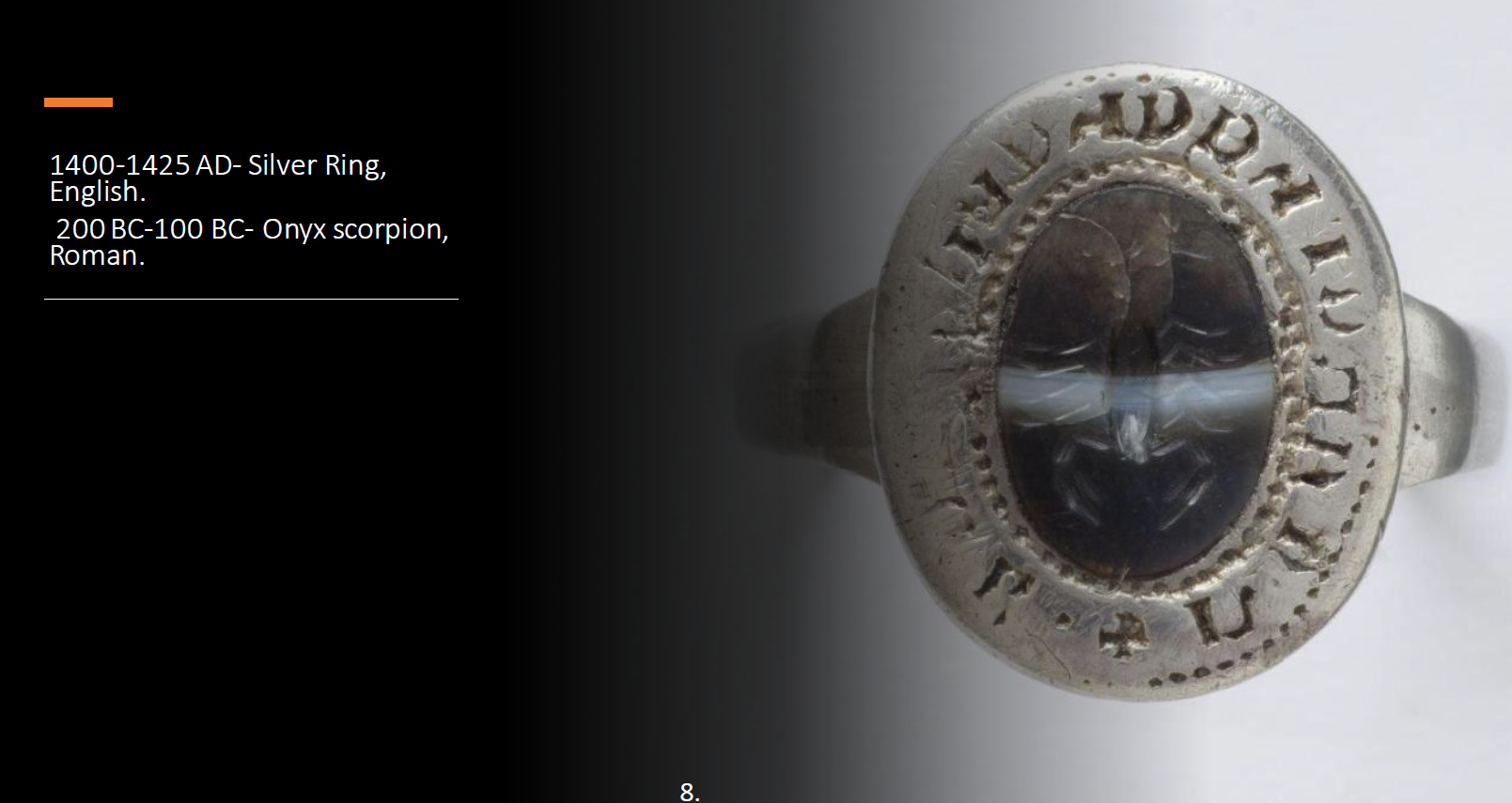

‘This scorpion intaglio dates from the 2nd or 1st century BC but has been reused in a medieval ring. Carved Greek or Roman stones were highly valued in the middle ages. They were found in excavations or in surviving earlier pieces of jewellery and traded across Europe. The scorpion had an enduring reputation as a protective amulet.’ (Wollheim, A, Dennis, M and F, 2006.)

This shares similarities to the Indian Tiger claw necklace, a fascination with a piece that would have held great power to the original artisans and wearers, but being redesigned and reinterpreted to suit a different time or place, the story continues to grow.

The underlying aspects of why these pieces were so important to the wearers cover many innate human needs.

To feel a certain protection or guidance in a world that can be so uncertain, to take control of ones fortune and feel secure while embarking through difficult situations. To hold onto something for hope of the future or hope to see a loved one again, whether magical or not, the faith that is placed in these items has throughout history given humans a sense of comfort when it is hard to come by through other means.

Many elements of protective symbols and amulets have continued to be filtered through to our own 21st century lifestyle, but can we truly say that we have that we are able to place the same level of faith and attachment in our own pieces?

A wise teacher once said ‘ If you picked out a piece of your jewellery, would you know what its made out of and where it’s from?’ (Hackett, M, 2021)

Developing a closer attachment to an object can perhaps be increased by knowing the story behind its components to assign your own meaning and personal story.

Pandora is one of the largest jewellery manufactures in the world, first founded in 1982 by danish man Per Enevoldsen and his wife. (Pandora group, 2021)

I’m sure we are all familiar with their mass produced charms promising the wearer Unforgettable moments. The same appeal of amulets and talismans applies to these charms that feature many ancient symbols of luck and protection, such as the indigenous American, dreamcatcher, to ward of nightmares. Four leaf clovers and horseshoes for luck as well as charms to ward of the evil eye.

Whether the owner is fully aware of the meaning or not, there is no denying the human desire to apply meaning and therefore tell a story with their keepsakes.

There can be a level of detachment when it comes to large jewellery companies, as truly finding a deeper connection with a piece will not entirely be achieved from mass produced items.

In order to find a missing link in the way we view our jewellery we must look to companies like Pandora and acknowledged the things that they are lacking.

To the everyday individual looking for a gift, they may never acknowledge this because it is hard to contend with the all encompassing saturation of the market, they may not even realise what they are missing.

As it falls to the artisan, the craftspeople, and the small business owners to remember to push the importance of custom, handmade, personal adornments. Perhaps the way consumers go about their gift shopping can change towards a more sentimental and sustainable future.

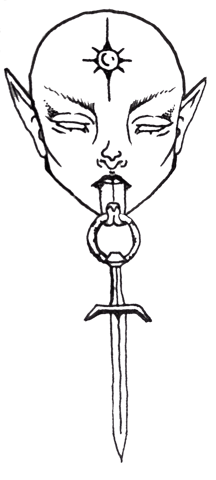

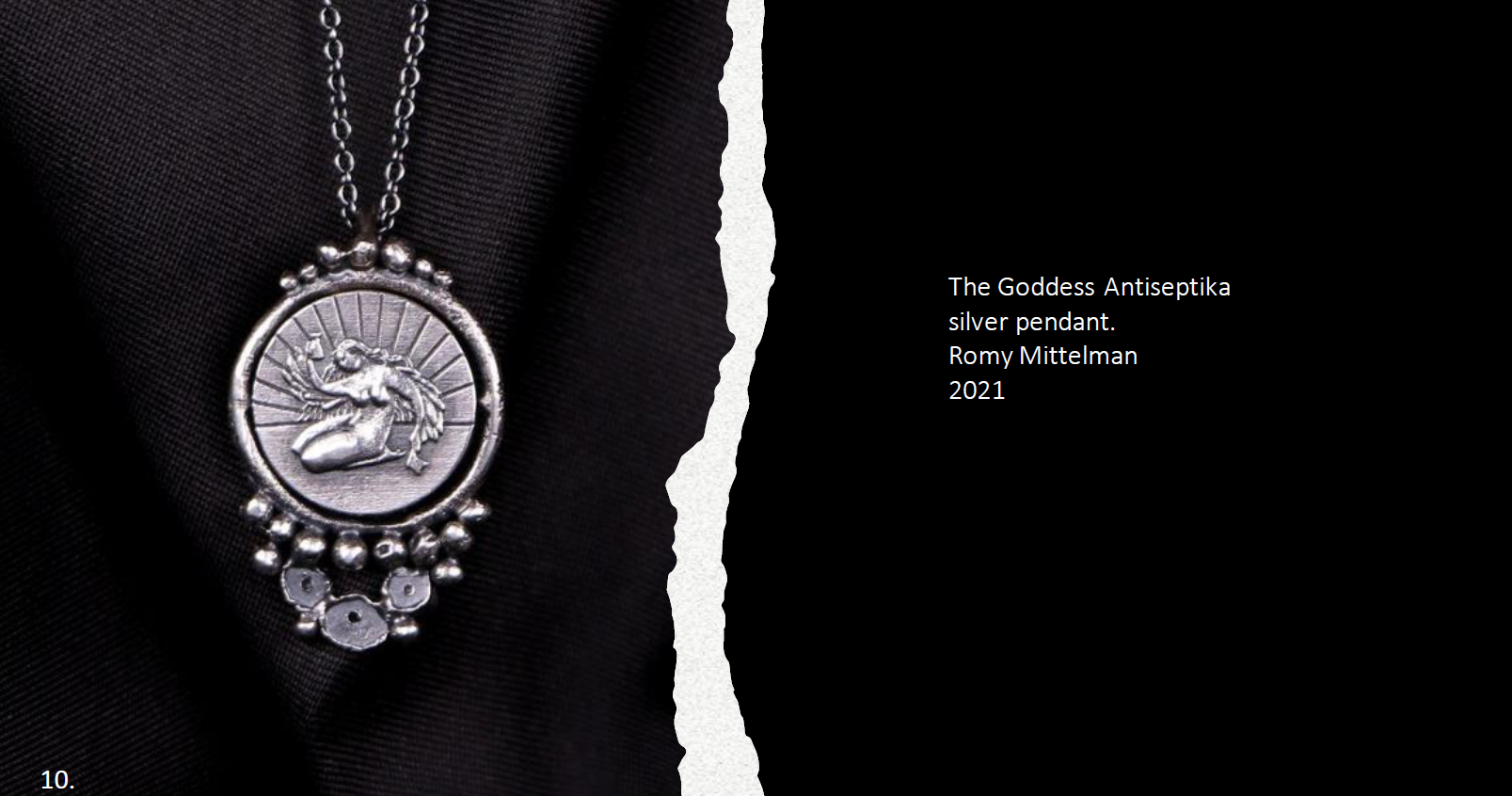

Romy Mittelman, a Melbourne based jeweller shows in her latest collection of lost wax cast jewellery featuring illustrations from Jennifer Hopper, a prime example of modern amulets and talismans. (Egetal, 2021.)

The range focusing on a mythological pantheon of female goddesses, each representing a different element of the struggle that we as a society are experiencing throughout the Covid-19 pandemic.

Creating a story/mythology, and assigning a meaning to these unique handcrafted pieces of jewellery is exactly what people throughout history have been drawn to when facing hardships that feel out of their control.

Many ancient amulets held power due to their rarity, in avoiding mass production we can hold onto an element of that, making these items even more cherished by the owner.

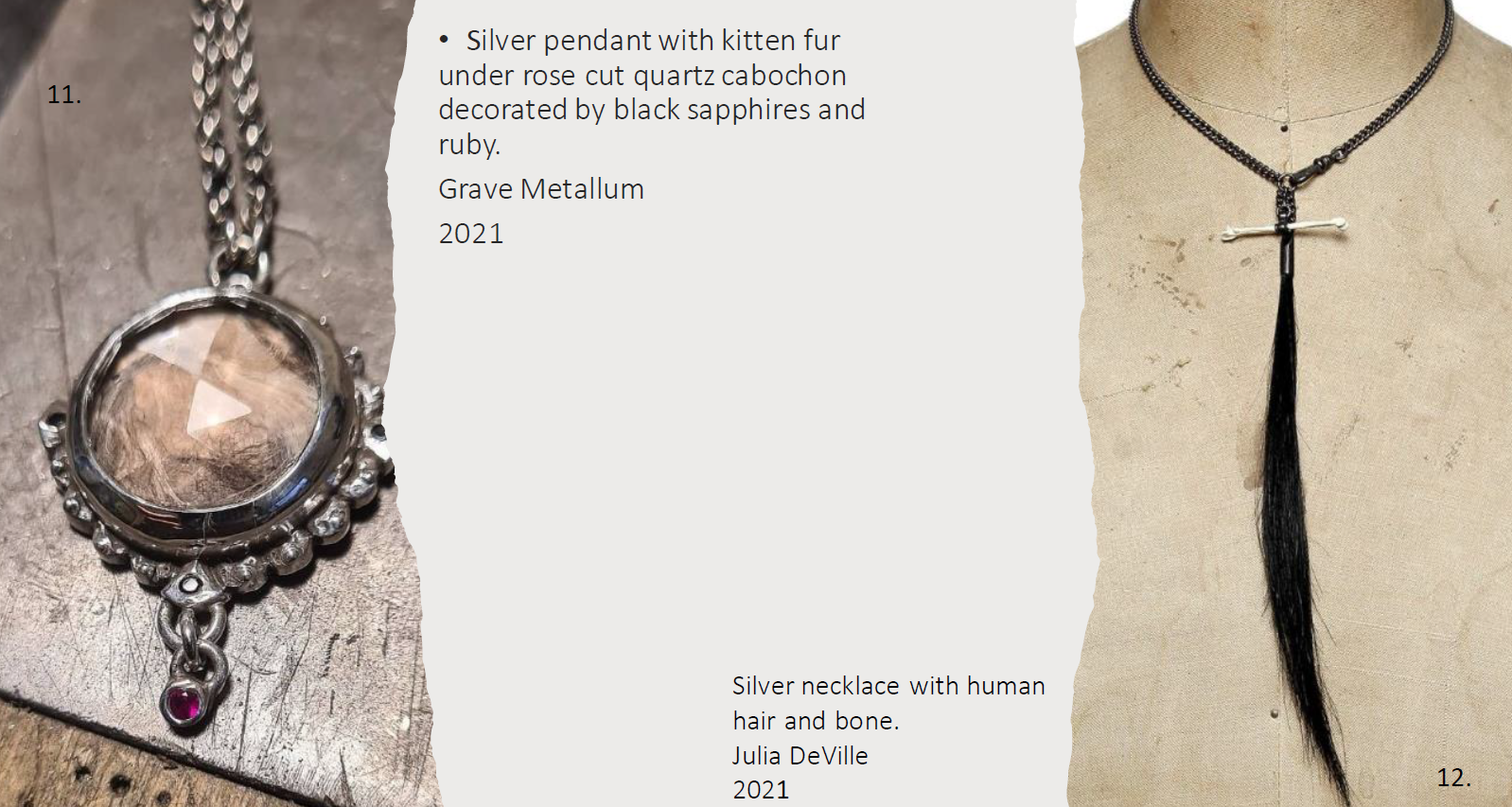

As seen in these pieces by Julia DeVille and Grave Metallum, they continue to incorporate fundamental elements seen in historical mourning jewellery and talismans.

The custom designed pendant featuring kitten fur from a clients lost pet, fully encapsulates these human desires to attach a deep level of meaning and the opportunity to tell a story as a way of coping.

Much the same in the human hair and bone necklace by Julia DeVille.

Perhaps it is time to reignite our sentimental, spiritual or dare I say superstitious spark. Understanding the meaning behind amulets and talismans and why they have been so important throughout history, may lead us towards acquiring our very own personal reliquaries to be passed down to future generations.

The same as Fanny parks creating a personal tiger claw amulet from her time in India, the same as the English and their fascination in Roman artefacts and giving them new life in updated creations. The same as in Bavaria and their hunting talismans, all the way to 2021 and the kitten fur pendant.

In understanding this, could we not apply this to our views on jewellery, instead of buying that Prouds the Jewellers ring for an anniversary present or Pandora charm, perhaps a custom made piece recreated from a family heirloom, or instead of a diamond, a sentimental keepsake under a glass cabochon.

The likely hood of these thought provoking adornments being forgotten or prematurely discarded is far less than mass produced store bought pieces. Choosing these sentimental materials that are already in circulation will take a little weight off the demand for mining precious gemstones that use valuable resources human and natural alike. (Archuleta, 2016)

‘sensationalising ‘things’ is attractive; the idea of looking back on the objects and practices of a mystical past is captivating.’ (Thwaite, 2019.)

_____________________________________________________________

Image References

Date pages viewed 1/10/21

Title Images from left to right-

L. J , Macarii, 1657, Abraxas, seu Apistopistus, Illustration, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Abraxas_seu_Apistopistus_-_Talisman_pg.068.png

R. WT, Pavitt, 1922, The book of talismans and zodciacal gems, Illustration, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Egyptian_talismans_Wellcome_L0004118.jpg

1. Victoria and Albert Museum, 2005,Ring, Horn, Toadstone, Silver, The Victoria and Albert Museum, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O115560/ring-unknown/

2. N.d., 1497, Extraction of a toadstone from the head of a living toad, Illustration, National Museums Scottland, https://www.nms.ac.uk/explore-our-collections/stories/natural-sciences/fossil-tales/fossil-tales-menu/toadstones/

3. Barnett, B, 2021, Charivari, Tusk, Hoof, antler, silver.

4. Victoria and Albert Museum, 2006, Ring, Silver, wolves tooth, The Victoria and Albert Museum, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O121221/ring-unknown/

5. Victoria and Albert Museum, 2004, Necklace, Gold, Tiger claw, The Victoria and Albert Museum, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O94038/necklace-unknown/

6. Victoria and Albert Museum, 1999, Locket, Gold, The Victoria and Albert Museum, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O11007/locket-unknown/

7. The British Museum, n.d., Mourning Ring, Gold, Enamel, Human hair, Glass, The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_AF-1648

8. Victoria and Albert Museum, 2006, Ring, Silver, Onyx, The Victoria and Albert Museum, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O121202/ring-unknown/

9. Pageant Updater, 2008, Pandora Bracelet, Silver, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=pandora+charm&title=Special:MediaSearch&go=Go&type=image

10. Egetal, n.d., Empress Antiseptika, Blackened Sterling Silver, Egetal, https://egetal.com.au/store/necklaces/romy-mittelman-empress-antiseptika-full-frame-spin-necklace-black/ (Permission to use received from maker.)

11. Grave Metallum, 2021, Kitten necklace, Sterling silver, Ruby, Fur, Black sapphire, Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/p/CQZmd3ktk_Y/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link (Permission to use received from maker.)

12. Julia DeVille, n.d., Hair necklace with bone, Oxidised sterling silver, enamel paint, human hair, Julia DeVille, http://www.juliadeville.com/shop/details/7329973059/hair-necklace-with-bone/ (Permission to use received from maker.)

____________________________________________________________________

Bibliography Date accessed 02/10/21

Works cited

-Archuleta J.L., 2016, The color of responsibility: Ethical issues and solutions in colored gemstones. Gems & Gemology.

- Bury, S, (ed.) 1984, Introduction to Rings, p.26, London.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O121221/ring-unknown/

- De Cuba, J, (ed.) 1498, Hortus Sanitatis (Garden of Health)

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O115560/ring-unknown/

- Encyclopedia Britannica editors, n.d., Amulets, Britannica, viewed 2 October 2021, https://www.britannica.com/topic/amulet

- Egetal, n.d., Empress Antiseptika, Egetal, 02/10/21, https://egetal.com.au/store/necklaces/romy-mittelman-empress-antiseptika-full-frame-spin-necklace-black/

- Moore, A W, (ed.) 1891, The folk-lore of the Isle of Man, London.

http://journal.sciencemuseum.ac.uk/browse/issue-11/a-history-of-amulets-in-ten-objects/

- Pandora group, 2021, The Pandora story, Pandora group, viewed 2 October 2021, https://www.pandoragroup.com/about/pandora-in-brief/the-pandora-story

- Stronge,S, Smith,N,J.C. Harle,(ed.)1988, A Golden Treasury: Jewellery from the Indian Subcontinent,Victoria and Albert Museum, Mapin Publishing, London.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O94038/necklace-unknown/

- Wollheim, A, Dennis, M and F, (ed.) 2006, At Home in Renaissance Italy, Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O121202/ring-unknown/

- Thwaite, A, 2019, ‘A History of Amulets in ten objects’, Science Museum group journal, Spring 2019, issue 11.

http://journal.sciencemuseum.ac.uk/browse/issue-11/a-history-of-amulets-in-ten-objects/

- Wippler, MG, (ed.) 1991, The complete book of amulets and talismans, Llewellyn Publications, Minnesota.